The 100 Greatest New York City Artworks, Ranked

When the artist Florine Stettheimer returned from a sojourn in Europe during the 1910s, she vowed to paint New York City as she saw it. She wrote a poem in which she spoke of a place where “skytowers had begun to grow / And front stoop houses started to go / And life became quite different / And it was as tho’ someone had planted seeds / And people sprouted like common weeds / And seemed unaware of accepted things.” She continued on, concluding ultimately that “what I should like is to paint this thing.”

She did so, producing works such as New York/Liberty (1918–19), in which downtown Manhattan’s busy port is shown with a chunky Statue of Liberty welcoming a ship. It’s a bombastic vision of all that New York has to offer, and it’s one of the works that make this list, which collects 100 of the best pieces about the city.

The works ranked below take many forms—painting, sculpture, photography, film, performance, even artist-run organizations whose activities barely resemble art. They pay homage to aspects of New York life across all five of its boroughs. Secret histories are made visible, the stuff of everyday life is repurposed as art, and tragic events from New York lore are memorialized. Binding all of these works is one larger question: What really makes a city?

These 100 works come up with many different answers to that query, not the least because a significant number of them are made by people who were born outside New York City.

Below, the 100 greatest works about New York City.

Cecilia Vicuña, “Sidewalk Forests,” 1981

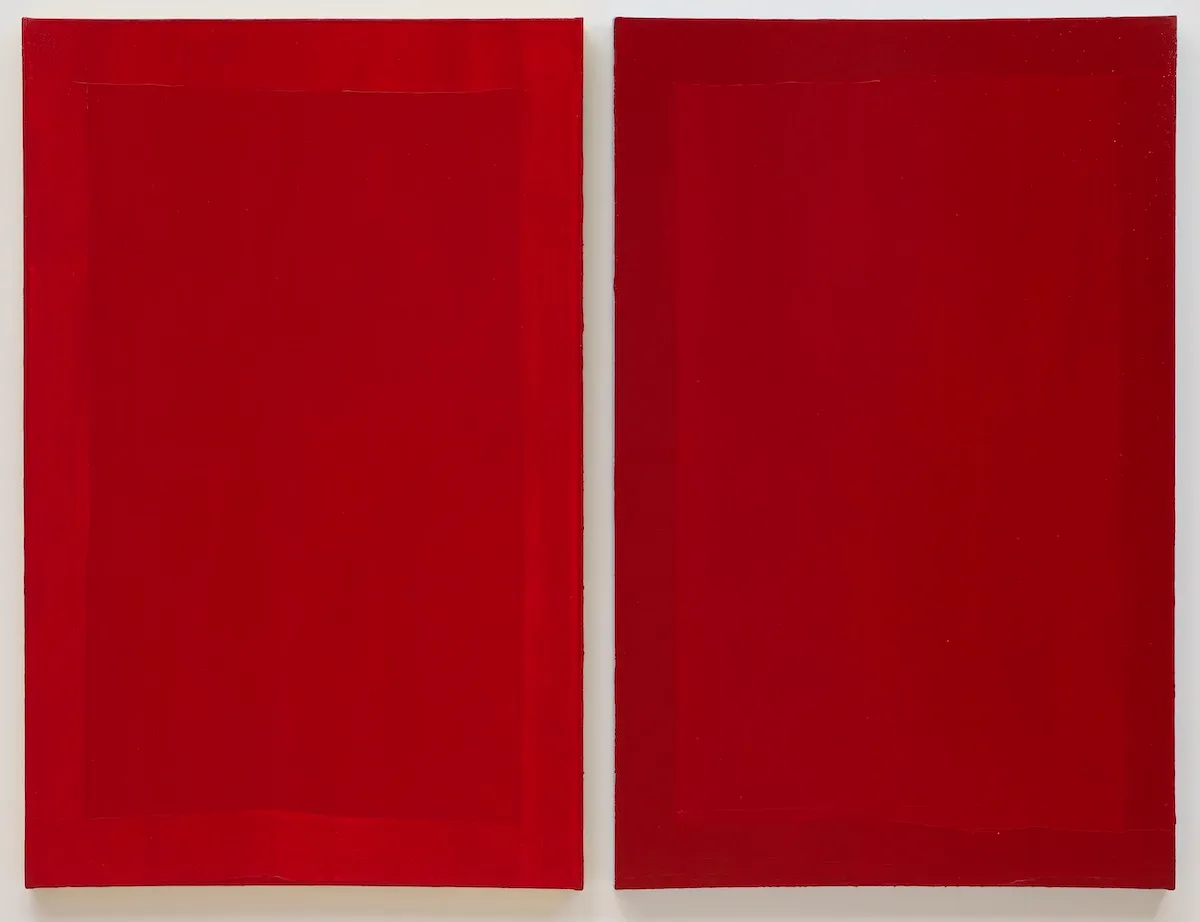

Mary Heilmann, Chinatown, 1976

This spare, elegant diptych, composed of nothing more than two red canvases placed side by side, may appear too abstract to represent anything even remotely New York–related. In fact, it alludes to Mary Heilmann’s experiences in the titular neighborhood, where she lived with three other artists in a building they rented for the meager sum of $500 a month. Seen that way, the painting is about cohabitation in New York, its two panels acting as a metaphor for what happens when people are cramped together in the city. Yet the work also looks back to the rich history of abstraction in New York, alluding to works by Josef Albers and Barnett Newman, the latter of whom even shopped at Pearl Paint, the supply store that was near Heilmann’s Chinatown loft.

Max Neuhaus, Times Square, 1977

Every day, all day long, the space below a pedestrian island in Times Square emits a low hum. This primordial sound—easy to miss amid the surrounding hubbub, and easy to appreciate once located—is an artwork by Max Neuhaus, a sound installation titled Times Square. It’s sited beneath a grate, which often leads people to write it off as stray noise from the N/Q/R subway line that runs belowground. In fact, however, it is intended as an environment, one that Neuhaus once described as being a “rich, harmonic sound texture resembling the after-ring of large bells.” Due to the development of the surrounding area, there have been periods during which the installation has been out of order. It is now owned by the Dia Art Foundation, which keeps it running.

Reginald Marsh, Pip and Flip, 1932

Many of Reginald Marsh’s most famous works are chaotic views of crowds on New York streets, where their bodies press up against one another, creating lines of densely packed people that have been compared to Greek friezes. In this one, a group of scantily clad women is assembled beneath advertisements on the Coney Island boardwalk. In his ribald paintings, Marsh generally does not pass up a chance to tease out eroticism, and here he pays close attention to the prominently placed, bared legs of his women. He also creates sly puns, pointing up ironies in the advertisements’ copy by casting a poster for a performer known as Major Mite—himself a man who stood just 2’4”—at a scale larger than anyone beneath it.

The scene’s namesake is a pair of Peruvian twins with microcephaly; the siblings were a popular attraction at Coney Island, where they were frequently exoticized in marketing from the era. One of the twins, Elvira, appears between two dancers who writhe around her. Notably, her actual appearance seems very different from her representation in the advertisement.

Ned Vena, Control, 2016

Ming Smith, James Baldwin in Setting Sun

Over Harlem, 1979

Jimmie Durham, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan is the World’s Largest Gothic Cathedral. Except, of course, that it is a fake; first by the simple fact of being built in Manhattan, at the turn of the century. But the stone work is re-inforced with steel which is expanding with rust. Someday it will destroy the stone. The Cathedral is in Morningside Heights overlooking a panoramic view of Harlem which is separated by a high fence., 1989

The cryptic title of this sculpture by Jimmie Durham sounds like an excerpt from a history of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, which is sited near where the artist lived in Spanish Harlem. The actual work doesn’t quite offer that. When he made this work, Durham, who said he was Cherokee, was inhabiting a persona known as the Coyote, a trickster figure in some Indigenous peoples’ lore, and was foraging Manhattan’s streets for skulls. He recalled finding a moose cranium in the cathedral’s garden and transporting it to his apartment building, where he had to saw off one antler to bring it upstairs. The practical decision ended up informing the artistic one, with Durham adding a pipe in the missing antler’s place, along with a wooden armature that now acts as something like a body. This, Durham later claimed, allowed the sculpture “to have a life but not taxidermy, not fake, but some sort of art life.” The elaborate play between fact and fiction extends to the work’s title, which includes at least one error: The real cathedral does not have a steel skeleton.

Fred Wilson, Guarded View, 1991

Guarded View does not explicitly represent any element of New York, but that is very much its point. It depicts the uniforms worn by guards at four institutions: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Jewish Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, all of which just happen to be located in Manhattan. The uniforms are worn by headless mannequins with no identifying features other than their skin tones, which are Black. Shown as art objects unto themselves, these uniforms point toward a line of work that frequently goes unnoticed by the general public. In exhibiting them within museums such as the Whitney, which owns Guarded View, Wilson makes visible one kind of labor performed by a largely nonwhite workforce—one of the many that help New York City run.

Jordan Casteel, Twins (Subway), 2018

In Jordan Casteel’s acclaimed group of paintings of subway riders in New York, people gaze on, hands clasp bags, and children play games with each other. In just about every case, Casteel’s subjects seem unaware of her. This is because Casteel has photographed them in secret, snapping pictures while herself taking the subway, then bringing these images back to her studio, where she paints tender homages to those who passed before her lens. In this painting, two children lie in slumber, slumped against a person who holds them both one hand. It’s a work that doubles as both an homage to the city’s sprawling mass transit system and a close-up to the moments of tenderness that often go missed while riding it.

Oto Gillen, New York, 2015–17

The images presented in this video by Oto Gillen have a quasi-apocalyptic air—they appear to be of our world but with slight, nightmarish alterations. During the course of its 107-minute run time, some 850 stills are shown, some for longer periods than others. There are photos of policemen and deliverymen, pictures of the unhoused, close-ups of people’s clothes, and more eccentric subject matter such as an image of a pretzel hanging on a street cart that’s illuminated in neon colors by an off-screen light source. Although many of these shots feel timeless, there are occasionally bleak reminders of recent events, such as one shot of a screaming Trump supporter. New York was projected floor to ceiling when it was exhibited at the Whitney Biennial in 2017, the year after Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election, and it retains its hypnotic power even in hindsight. It stands as a time capsule from a city on the brink of collapse during a pivotal moment in U.S. history.

Shu Lea Cheang, Fresh Kill, 1994

Issues related to climate change and the oppression of certain communities in New York are broached in the prescient Fresh Kill, an experimental film by Shu Lea Cheang that preceded her later works shown in art spaces. Sarita Chowdhury and Erin McMurtry star as a lesbian couple living on Staten Island near the Fresh Kills Landfill, which at the time had attracted scrutiny because of how much trash it had accrued. (The landfill is no longer active.) Midway through the film, for reasons that remain somewhat unclear, the couple’s daughter is kidnapped, possibly in connection with a shadowy corporation that has besieged New York with pollution. Hacking gradually becomes a form of resistance for this couple—and suggests a potential way to survive in a rapidly changing city, reversing the power dynamic that keeps queer people, people of color, and lower-class communities out of view of the city’s elite.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Gates consisted of portal-like forms from which large swatches of saffron-colored fabric were hung in Central Park. That fabric, which took about a year to install, billowed gently in the wind, its sharp color making for a neat contrast with the winter snow covering the ground in February 2005 when the installation was completed. The Gates was one of the duo’s biggest installations, spanning paths that ran all across the park. Attempting to see it all would have taken hours of walking, but the millions who viewed the work seemed content to experience even a part of it. According to New York officials, The Gates was a smash hit, with some estimating that it generated $80 million for the local economy.

Lee Quiñones, Stop the Bomb, 1979

Between 1974 and 1984, Lee Quiñones and a team of young collaborators painted entire subway cars with sprawling, colorful messages, leaving MTA officials aghast at how the artist had managed to pull off these works without anyone noticing. While the cars remained operational, they were eventually cleaned of Quiñones’s spray-painted imagery, which now remains only in the form of photographic documentation by Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper. One such work was Stop the Bomb, an antiwar piece alluding to the then-ongoing Cold War. It reminded its viewers that “man is almost extinct” and encouraged action to halt the conflict before another atomic bomb goes off. Quiñones has said that his subway-car pieces were an attempt to create a visual record for a community in the Bronx that “didn’t necessarily have any art history to stand on.” In doing so, he brought art out of New York’s most august institutions and into the public space.

Pena Bonita, Hanging Out on Iroquois and Algonquin Trails, 2015

In addition to working as an artist, Pena Bonita, of Apache and Oklahoma Seminole descent, was once a licensed tour guide on buses that transported sightseers across Manhattan. The job afforded Bonita an understanding of how little many of the out-of-towners knew about the city—most notably about the Indigenous peoples who called the land home before it was taken away from them and built up by settlers. This history informs Hanging Out on Iroquois and Algonquin Trails, a group of 16 burlap sacks that each bear the name of a lower Manhattan street. Stuffed with shredded money, the sacks dangle from fabric knotted around a long element sculpted to resemble a snake. The piece lays bare the hidden past of the Financial District. “Mohawks, Canarsie, Lenape, Ramapo, and other tribes traded on what is now Broadway,” Bonita told American Indian magazine. “Money enclosed in the hanging bags are references to the historical exploitation of New York and the current wealth that still profits from this historical exploitation.”

George Tooker, The Subway, 1950

In The Subway, any sense of aboveground New York glamour melts away as a nagging anxiety takes over underground. The subway seen here isn’t explicitly New York’s—there are no signs for the MTA and no indication of what station stop this is. But when George Tooker painted this work, he was based in the city, and certainly this station’s turnstile recalls many that can be seen throughout the New York subway system. The architecture of Tooker’s station is deliberately nonsensical, however, with a hallway that extends deep into the distance and alcoves in which people can hide. Men and women are dotted all over, but this subway isn’t meant to transport people; it’s meant to keep them trapped. Tooker’s painting expresses the alienation and fear that many felt in New York during the postwar era.

Anicka Yi, Force Majeure, 2017

Like many of Anicka Yi’s most famous works, Force Majeure was alive. Literally. The splotches lining its agar-coated tiles were not produced by paint but by bacteria, which were allowed to grow throughout the period the piece was on view at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. These bacteria were sourced from the city’s Chinatown and Koreatown neighborhoods and were then given second life in a refrigerated environment on the Upper East Side. In allowing the bacteria to grow of its own accord, Yi asserted the piece as its own ecosystem, both beautiful and self-sustaining—not unlike the two majority-Asian neighborhoods she was drawing on.

Ahmed Morsi, Subway Station III, 2015

Lucia Hierro, Sweet Beans (Habichuela Con Dulce), 2017

Many of Lucia Hierro’s works bring elements of the predominantly Dominican neighborhood of Washington Heights into gallery spaces. For Hierro, this is one way to uphold a culture that has largely been invisible in mainstream art venues around New York. Sweet Beans is one of Hierro’s “Mercado” works, a series of wall-hung sculptures that she made with her mother, who “saw herself and her community reflected in the work, and her approval overshadowed that of any art critic,” Hierro once said. Sweet Beans is intended to resemble a bag filled with ingredients for habichuela con dulce, a sweet dish typically consumed during Dominican Lenten season. The objects held in Hierro’s sack—oversize replicas of Goya and Badia products—will be recognizable to anyone who’s ever walked into a New York bodega. Here, rather than being sold for a few dollars apiece, the products are raised to the status of high art.

Jack Whitten, NY Battle Ground, 1967

The abstraction of Jack Whitten’s NY Battle Ground conjures the chaos that the artist—and many others—faced during the late 1960s, a time when images of the civil rights movement, activism on college campuses, and the Vietnam War hit the airwaves daily. In 1967, the year he painted it, New York was roiled by protests over the shooting of Renaldo Rodriquez by an off-duty police officer in Spanish Harlem. The tense week that followed saw hundreds of Puerto Ricans march in the streets and a general sense of unrest. Although Whitten’s painting does not explicitly depict any of this or even respond directly to it, the piece does crystallize the sense of anxiety that followed Rodriguez’s killing, with swirling forms recalling helicopters darting across the sky, possibly to perform surveillance, possibly to cover the scene for those watching the evening news. NY Battle Ground shows how some moments of the city’s history exist beyond figuration, leaching into the public consciousness in unexpected, inexplicable ways.

George Bellows, Forty-two Kids, 1907

When George Bellows’s Forty-two Kids debuted, it proved controversial, not because of its child nudity, as contemporary audiences might expect, but because of its subject matter. The painting’s title terms the bathing boys seen here kids, a word that, at the time in New York, referred to lower-class youngsters associated with crime. In offering a brushy view of them at the edge of the East River, Bellows claimed to be simply representing what he saw. Critics viewed these children as unhygienic and animal-like, however, and the negative perception even caused the painting to lose out on esteemed art prizes. Today, Forty-two Kids holds a different reputation, as a defining work of the American realist movement of the early 20th century.

Loretta Fahrenholz, Ditch Plains, 2013

Hurricane Sandy, which killed 44 New Yorkers and resulted in an estimated $19 billion in damage in 2012, haunts Loretta Fahrenholz’s video Ditch Plains. Its ostensible subject is neither the hurricane itself nor the destruction it caused; instead, it shows a group of mostly Black dancers, among them Ringmasters Corey, Jay Donn, and Marty McFly. They perform a dance style known as flexing, and they enact their jerky, disconcerting movements across a stretch of Brooklyn known as East New York. Lensed in the weeks following Hurricane Sandy, Fahrenholz’s images are bathed in darkness, and at times her film goes full-tilt into horror, with a foreboding soundscape that occasionally includes a garbled voiceover. Ultimately this video asserts that, even in the face of disaster, New York communities continue to exist; they just may appear very different from how they did before the storm.

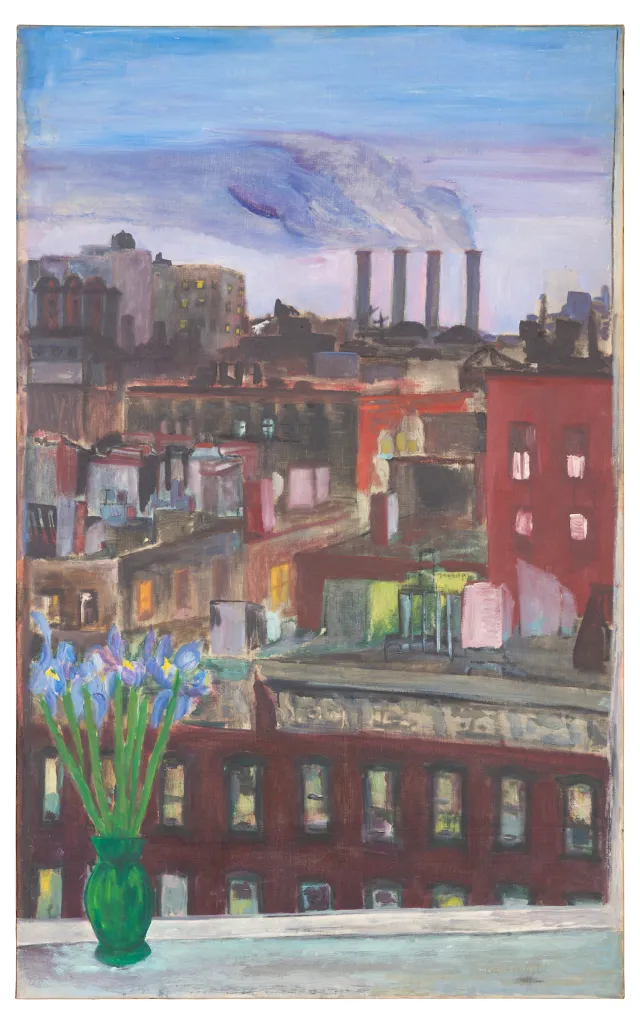

Jane Freilicher, Early New York Evening, 1954

During the 1950s, at a time when Abstract Expressionism was in and figural painting was out, Jane Freilicher worked in a naturalistic mode, offering quaint views of the city as seen from the penthouse of her Greenwich Village apartment. The artist and critic Fairfield Porter once termed Freilicher’s paintings “radical,” and Early New York Evening makes obvious why. The foreground of this flattened view of Manhattan features a vase with bluish flowers, the only natural element in a scene dominated by urban structures. Freilicher includes several smokestacks that belch their contents into the sky, disturbing the layers of purple that constitute a sunset. The painting is also about stilled time. Close looking reveals that some windows are lit up while others are not; Freilicher has captured that very short period of a day’s end when people are just starting to get ready for the night.

Maren Hassinger, Pink Trash, 1982

By the time Maren Hassinger staged her performance Pink Trash, she had repeatedly made use of pink in her art. “For me,” she once said, “the color pink is not about being a woman, but more about choosing a color with the power to compete with the green of nature.” She did just that with Pink Trash, for which she picked up litter in fields in Central Park—and, later, also in Van Cortlandt and Prospect Parks. She then painted that refuse pink. While wearing an outfit in that color, she strewed the trash about in the fields from which it came, enacting and subverting a ritual undertaken by the city’s many maintenance workers. In their new form, the cigarette butts, crumpled papers, and more stood out on the green grass. Hassinger’s performance highlighted what we choose to see in terrain familiar to many New Yorkers—and how easily that terrain can be altered through the slightest of interventions.

Alan Michelson with Steven Fragale, Sapponckanikan (Tobacco Field), 2019

In 2019 the Whitney Museum’s pristine lobby became host, albeit digitally, to a field containing tobacco of the sort that was once harvested by the Lenape in what is now Manhattan’s Meatpacking District. These computer-generated plants could be seen by way of an augmented reality installation called Sapponckanikan (Tobacco Field), which Alan Michelson produced in collaboration with Steven Fragale. Museums in New York, like most other spaces in the city, have long ignored the fact that they are sited on unceded Lenape land; it wasn’t until 2021 that the Metropolitan Museum of Art added a land acknowledgement to its facade. But Michelson, a Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River, sought to lay New York’s Indigenous history bare—and even to make it come alive. Over the course of the three and a half months Sapponckanikan was viewable via cell phone in the Whitney’s lobby, the tobacco plants appeared to grow until they towered over people’s heads.

Nikki S. Lee, The Tourists Project (9), 1997

In an effort to avoid the camera-toting tourists who crowd the streets of Times Square and other nearby locales, many New Yorkers try to steer clear of Midtown. Nikki S. Lee, however, took a different approach during the 1990s, when she remade herself as a tourist and ingratiated herself to the out-of-towners. For this photograph, Lee dons a backpack, shorts, sneakers, and athletic socks and poses beside others in similar clothing. Lee was born in Seoul but by this point was based in New York. In refashioning herself as a sightseer, had she truly rid herself of her identity as an outsider of the Asian diaspora? Later works by Lee, in which she performed as trailer trash or a Black or Latina person, continued to pose this question, sometimes in ways that critics have questioned due to their elements of race play and cultural appropriation.

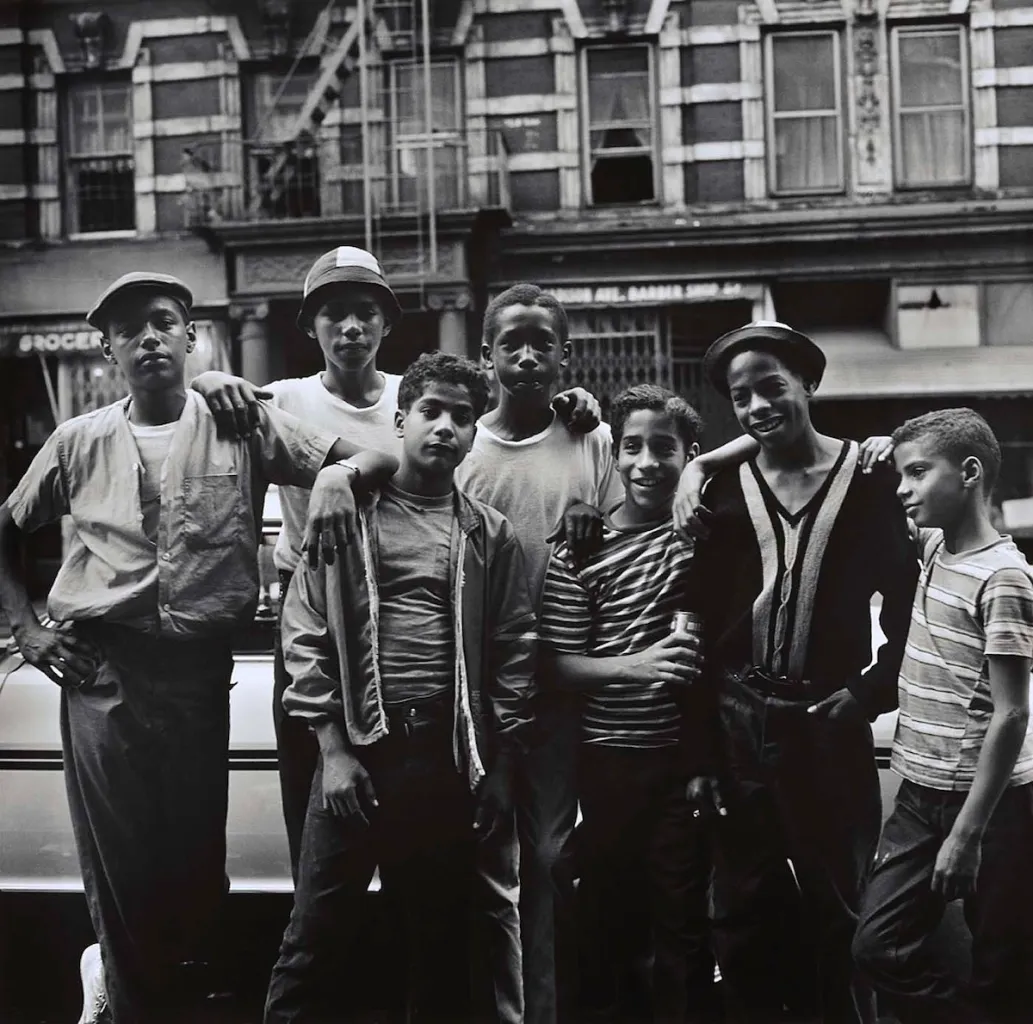

Hiram Maristany, Group of Young Men on 111th Street, 1966

There is a long history of documentary photography in New York, but only rarely have the artists behind the images held a direct relationship to the communities they pictured. Hiram Maristany’s dynamic images of Nuyoricans in East Harlem are somewhat different. Maristany, who acted as a photographer to the Young Lords and later directed El Museo del Barrio, turned his lens on members of his own community with unusual compassion, in an effort, he once said, to disentangle people who looked like him from racist stereotypes about Puerto Ricans. Images such as this one, featuring an arrangement of young men who stare back at the camera, meeting the viewer’s gaze, combat those negative images by presenting Nuyoricans as they actually were.

The location where this picture was shot was one Maristany returned to frequently because he knew it well. “It’s no accident that a lot of the images are of 111th Street,” he told the Smithsonian Institution in a 2018 interview. “That’s the street that I was born and raised on.”

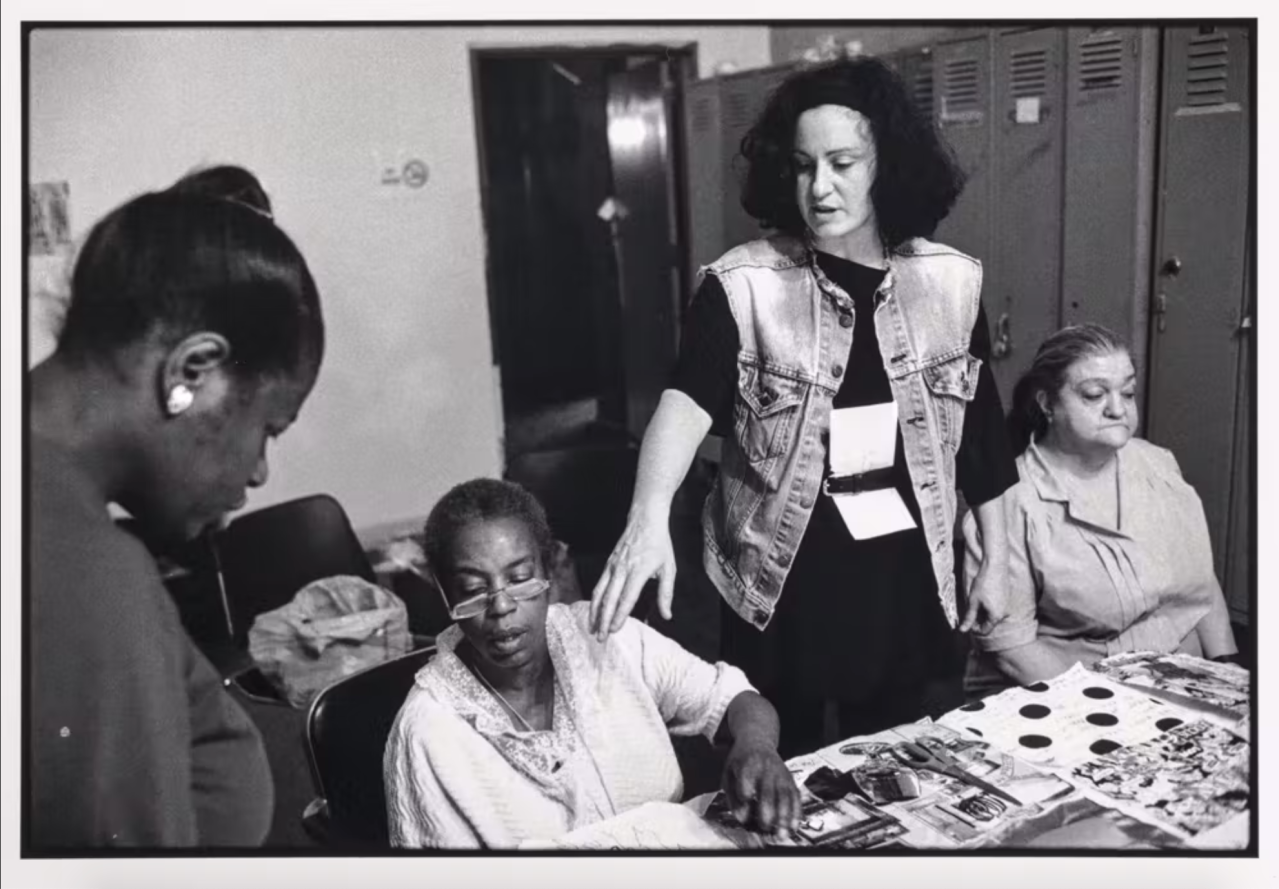

Hope Sandrow, Artist & Homeless Collaborative, 1990–95

Hope Sandrow’s Artist & Homeless Collaborative no longer exists, and even when it was active, it could not be contained within a gallery’s walls. In fact, some may not think it counts as artwork because it functioned more like activism. As its name would suggest, the Artist & Homeless Collaborative aided the unhoused of New York, a group whose visibility has rarely been acknowledged by the art world. Its focus was specifically women at the Park Avenue Armory shelter, who were paired with artists such as the Guerrilla Girls, Rigoberto Torres, Pepón Osorio, Ida Applebroog, and Kiki Smith to make art together. The work that resulted could not fix these women’s condition, but it did lend them a conduit for transmitting their voice to the general public.

Jennifer Bartlett, Goodbye Bill, 2001

As Jason Farago pointed out in a New York Times article marking the 20th anniversary of 9/11, there are not many artworks that depict outright the attacks on the World Trade Center, a tragedy that is still extremely difficult to bear. Jennifer Bartlett’s painting Goodbye Bill is a rarity because it so explicitly portrays the day’s painful events. In it, the North Tower is shown collapsing amid a plume of smoke; among those killed was the painting’s namesake, the photographer Bill Biggart, who died taking pictures for the press. Just barely visible amid Bartlett’s gridded dots is a small figure that appears to have jumped from the skyscraper, as so many did that day in a desperate attempt to escape. While Bartlett’s painting may dissolve into abstraction, this person remains crystal clear, a reminder that the deaths that occurred on September 11 will never be totally forgotten.

ART CLUB2000, Untitled (Times Square/Gap Grunge 1), 1992–93

Many of the jokey activities of the short-lived collective ART CLUB2000 centered on The Gap, a clothing company whose omnipresence was ascendant during the 1990s, with advertising appearing seemingly everywhere in New York. Rather than rejecting The Gap’s ubiquity, ART CLUB2000’s members embraced it, donning the company’s clothes with a mix of genuine fascination and tongue-in-cheek irony for a series of works that now exist only as photographic documentation.

In this photograph of the artists in Times Square, the members wear calculatedly cool uniforms of denim vests, gray sweatshirts, frayed jorts, red bandanas, and sunglasses. Situated beneath a crush of marquees promoting Diet Coke and Canon, the artists seem like walking ads—people who are selling consumer goods while also selling themselves out. “In all of our photos that year,” members Daniel McDonald and Patterson Beckwith told Artforum in 2013, “we looked for locations that would backdrop our own ambivalence about a romanticized urban lifestyle that was totally artificial.”

Hedda Sterne, NY, NY No. X, 1948

Yayoi Kusama, Naked Demonstration/Anatomic Explosion, 1968

These days, Yayoi Kusama’s name conjures Instagram-worthy “Infinity Rooms” lined with dots. During the 1960s, however, she made herself known with agitprop performances that contained explicit political sentiments. Naked Demonstration/Anatomic Explosion, one of these works, was done in protest of the Vietnam War, which Kusama and many other artists viewed as a threat to a sense of unity that had been felt during that era.

Using a tactic borrowed from hippie culture, she assembled a group of nude performers outside the New York Stock Exchange and had them flail about while a person struck a bongo. (Kusama herself didn’t strip down, remaining clothed in garb lined with her signature dots.) “OBLITERATE WALL STREET MEN WITH POLKA DOTS,” a press release read. “OBLITERATE WALL STREET MEN WITH POLKA DOTS ON THEIR NAKED BODIES. BE IN . . . BE NAKED, NAKED, NAKED.” This gesture took place more than 40 years before Occupy Wall Street and seems all the more prescient because of it.

ARTnews was unable to obtain permission to run Shunk-Kender’s documentation of this work. This work can be found on the website of the Museum of Modern Art, which owns it.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura: Times Square in Hotel Room, 1997

Early in his photography career, Abelardo Morell hit on a formula he would come to use over and over: He would cover a room’s window with black plastic, create a small aperture in it, and allow the light from outside to flood in. He would then position his camera facing a wall and take an extended time exposure of the image projected on it.

This photograph, which took two days to produce, was shot in a suite of a Marriott hotel in Times Square—the kind of placeless space that generally lends itself to short stays by anonymous tourists. While that room would typically conjure a quiet respite from the raucous streets, Morell’s camera obscura forces the exterior noise inward, with loud advertisements for Phantom of the Opera, Rent, and other Broadway mega-productions now lining the wall. Morell, whose family moved from Cuba to New York during the 1960s, has pointed out the lack of humans seen alongside the ads, telling the New York Times, “Think about how many people go through this site in two days—millions—and no one stood still long enough to get seen. It’s so empty, almost a perverse picture.”

Bumpei Usui, Bronx, N.Y., 1924

The Bronx viewed in Bumpei Usui’s 1924 painting is very different from the Bronx one sees today. Indeed, Usui, a Japanese-born artist who had moved to New York just three years earlier, sought to capture a borough going through a transition. His Bronx looks like a construction site, with bricks and rigs interrupting the rolling hills. By comparison to bustling downtown Manhattan, which Usui also depicted in other matte-finished paintings, the Bronx is a work in progress, an area undergoing a modernist remake.

Usui, who was also a furniture maker, had his works shown alongside artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Charles Demuth. Like Demuth, Usui has been labeled a Precisionist, a term used to describe the metallic, jagged, hard-edged look of the elements in his paintings. In the case of Bronx, N.Y., even the trees appear industrial, the look of their foliage rhyming with that of the tubes piled into a pyramid in the foreground.

James Van Der Zee, Couple, Harlem, 1932

Helen Levitt, NYC, ca. 1940

During the late 1930s and early ’40s, Helen Levitt helped define documentary photography by bringing her light, handheld camera into relatively poor New York neighborhoods. What she captured looked little like photojournalism, however. This photograph features a group of children heading out for Halloween festivities, although the picture itself doesn’t disclose much about what’s taking place. Levitt’s attention is directed toward the psychologies of these kids, who all appear richly defined, even if we can’t see their faces. The one at the top of the stairs is still putting on her mask and does so with awkwardness and innocence, while the one at the right looks off into the distance with assurance, perhaps signifying that he is older or at least more mature. In their masks, these children appear supernatural, like specters transported to a New York we know all too well.

Mark Dion, The Department of Marine Animal Identification of the City of New York (Chinatown Division), 1992

There is no actual Department of Marine Animal Identification of the City of New York, and Mark Dion is not a scientist. But for this work, the artist took up the guise of one, using this installation composed of a desk, a map, a cabinet, a chair, and more as an informal office in which to identify sea creatures found in Chinatown. During the run of a solo show at the storied American Fine Arts gallery in New York, Dion would himself be on hand to categorize the animals he encountered, some of which were stored in jars. Like many of his other works from the era, this piece is about modes of classification and the ways that certain objects and beings will always evade them. Dion has recalled that he had a hard time fitting all the animals into a predetermined biological rubric, saying that the work is about “the struggle—how difficult it is for me as a layperson to adopt or shadow some elements of the methodology of another discipline.”

Ei Arakawa with Gela Patashuri, NYC Corrals & Iwaki Ocean’s Temporal Visit, 2021

In June 2020, when New York began stirring again at the end of a Covid lockdown, an unfamiliar sight began appearing on the city’s streets: temporary outdoor dining structures intended to help stem the spread of the virus. These structures made their way indoors at Artists Space, a hallowed alternative art center, for a show in 2021 by the Japanese-born Ei Arakawa, who enlisted Gela Patashuri, a native Georgian, to construct them according to a rigid set of rules put out by the city. Alongside Patashuri’s wooden elements, which Arakawa termed “corrals,” a stream of water snaked through a makeshift chute that ran along a wall and into a basin on the floor. Arakawa had his mother and brother in Fukushima send him this water from his home country. With its cool trickle, the piece acted as a serene reminder of the barriers that many transplants in New York continue to face.

Paul Cadmus, Greenwich Village Cafeteria, 1934

In this painting, unnaturally voluptuous figures twist and turn across one another in a crowded eatery. A woman reaches for a fallen purse, her arm nearly hitting a soused man’s leg, while several others gab passionately. Meanwhile, a waiter serves a cup of coffee that comes perilously close to sliding from his tray. Even though it all feels fantastical, the scene was based on a real-life Greenwich Village café that Cadmus himself frequented. Evidence of this can be spotted at the far right, where a man with pink nails and a conspicuous ring ventures knowingly behind a door marked “MEN”—a blatant allusion to the queer subculture that Cadmus, an out gay man, knew well.

André Cadere, New York, November 1975, 1975

These days, André Cadere occupies cult status among artists for performance-like pieces (such as the one seen here) in which Cadere toted around a colorful stick—he called it a barre de bois ronds (“round wooden bar”)—in locations in New York, London, and Paris. He termed these acts promenades. All that exists of the promenades now is photographic documentation, his barres appearing in the New York City subway, leaning against the fence of a basketball court, and so on. Cadere, who died in 1978, is no longer with us, but the promenade pictures he left behind act as emblems for all the people who have gone on their own personal voyages across New York, briefly touching the city around them in the process.

Cameron Rowland, Van Cortlandt Park, 2021

Visitors to Cameron Rowland’s 2021 show at Essex Street gallery were encouraged to visit the nearby Seward Park on the Lower East Side, where several artworks were on view. Most critics reported trouble finding the works there because, as it turned out, they were replica benches that looked exactly the same as preexisting ones in the park, with two subtle differences: They were not bolted to the ground, and they had not been authorized.

One of these benches, Van Cortlandt Park, was sited near a playground, where its dark context could easily have been overlooked. This bench and the others Rowland exhibited were references to Black burial grounds throughout New York, one of which is believed to have been located in the piece’s namesake Bronx park. (Van Cortland Park officials have acknowledged that a “substantial” number of bodies may be buried there.) Rowland then connected that history to the man who lent Seward Park its name, William H. Seward, who, despite claiming to be an abolitionist, tried to quash the 15th Amendment, which grants all Americans the right to vote regardless of race. Rowland’s bench materializes a history that has long been kept invisible by those in power. It will remain on view indefinitely, in an assurance that that history will not easily be forgotten.

Kwame Brathwaite, Photo shoot at a public school for one of the AJASS-associated modeling groups that emulated the Grandassa Models and began to embrace natural hairstyles, ca. 1966

Seen from today’s perspective, this photograph could easily be misconstrued as an image from an editorial spread in a fashion magazine. At the time it was taken, however, dark-skinned Black women like the ones shown here did not regularly appear in those publications, even ones like Ebony, where light-skinned models were still the norm. Seeking to upend that, Kwame Brathwaite took his camera to Harlem, where he photographed residents in styles that were unmistakably local. Brathwaite’s collaborators sourced his models from Harlem’s streets; he grouped them under the name Grandassa, an allusion to politician Carlos Cooks’s term for Africa. In this shot, the artist shows women who have absorbed styles put forward by the Grandassa Models on the runway, proudly sporting natural hairstyles. By posing these models outside, Brathwaite establishes a connection between that neighborhood and the women who shape it.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Homeless Vehicle, 1988–89

During the 1980s, Krzysztof Wodiczko diagnosed a problem in New York: The rich were getting richer and the poor were getting poorer, and the growing divide between the two was being expressed physically, in the form of designer objects and gleaming skyscrapers like Trump Tower. In 1988 this sculpture ended up being paraded before Trump Tower by an unhoused man. People like him were invited to work with Wodiczko as “consultants” on the piece, a conical container with fencing that could act as a bed, a lavatory, and a storage unit. The people whom Wodiczko enlisted to cart it around became something like performers; some embraced the work, while others voiced acute anger about the project, according the artist. Homeless Vehicle is a work that points up a sad contradiction. This is an object that should not have to exist at all, and yet here it is, designed not by a state-appointed official but by an artist acknowledging a group of people the city has generally been unwilling to support.

David Diao, Kowloon / Lower Manhattan, 2014

David Diao came to New York from Hong Kong in 1955 and has remained in Manhattan ever since, working from a loft building in Tribeca where he also lives. Reflecting on his diasporic life, Diao has often painted works that place the histories and art of New York and China, where he was born, alongside each other. Kowloon / Lower Manhattan is composed mostly of two maps, one portraying the district where he lived as a child in Hong Kong, the other showing the bottom portion of Manhattan, with a yellow dot on both to note where he resided. The two maps have vague resemblances, and Diao seems to make a point of their similarities. But the painting also mourns the erosion of history. Both maps are partial, the New York one notably cutting off just before the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges. Cast against blue and aqua expanses that hint at the ocean and allude to Color Field abstraction, these maps survey geography familiar to Diao while also suggesting that much has been lost to him over the years.

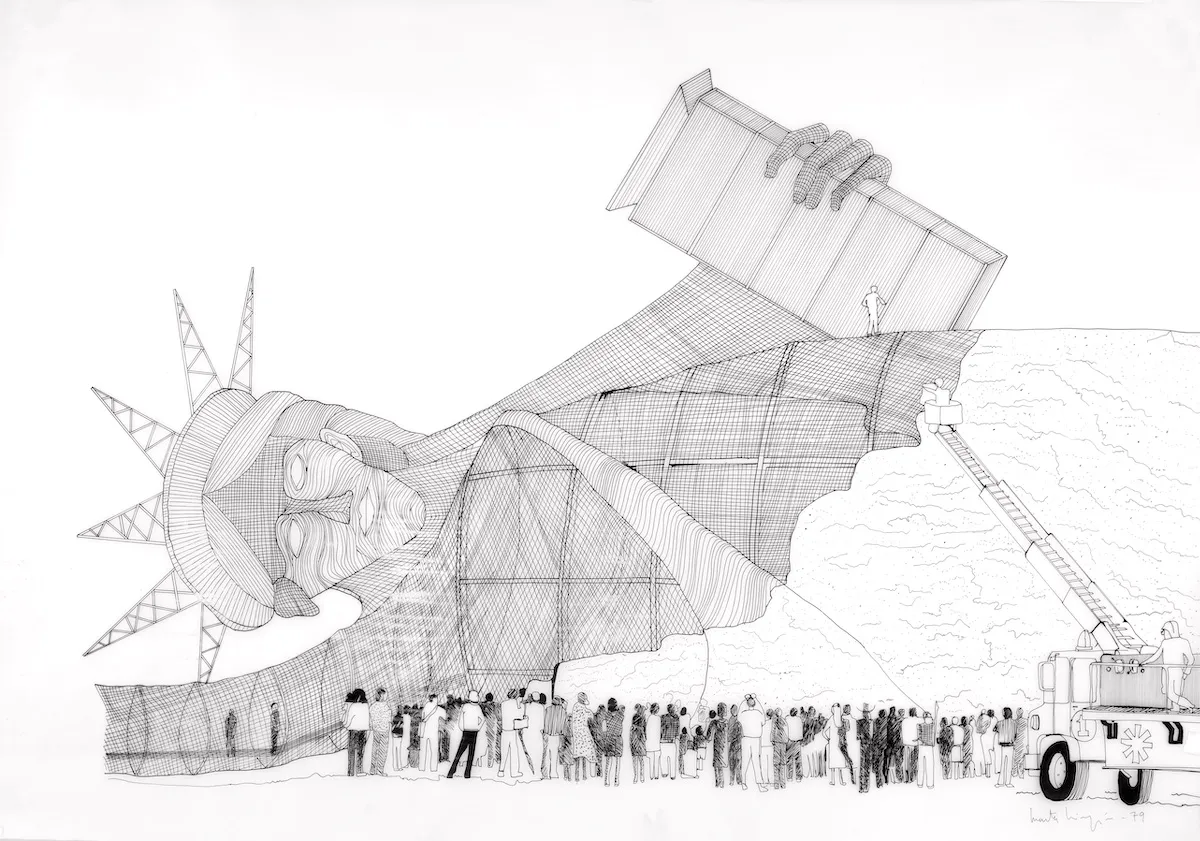

Marta Minujín, Statue of Liberty Covered in Hamburgers (Estatua de la Libertad recubierta de hamburguesas), 1979

In Buenos Aires, the city where Marta Minujín was born, the artist found herself fascinated by the Obelisco, a 235-foot-tall structure that she fashioned anew for a sculpture of her own. She covered it in Panettone sweet breads, a food she associated with Argentina, and let viewers feast once her obelisk was lowered. Seeking to re-create the project in New York, where she moved during the 1960s, Minujín turned her eye toward the Statue of Liberty, whose likeness she wanted to build in Battery Park using an armature so large that viewers could walk into it. She sought to cover it in hamburgers, which would be grilled using a flamethrower, and to source the patties from McDonald’s, to whom she a penned a proposal, beginning, “I write to you because I have an idea to be made with hamburgers.” Her idea was never realized—it exists now only as sketches—but this has not stopped many from obsessing over the project. Curator Connie Butler has labeled it a feminist subversion of a phallic symbol, while others have read it as a tongue-in-cheek parody of what constitutes American identity.

Weegee, Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, ca. 1942

There is no shortage of memorable mishaps that have taken place at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade—that time in 1991 when Kermit the Frog deflated, for one. But even an average Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade is strange enough, and leave it to Weegee, one of the great chroniclers of New York absurdity, to point that out. The Museum of Modern Art, which owns a print of this photograph, estimates that it was shot around 1942, which would mean Weegee snapped it around the time that the parade was called off, due to a helium and rubber shortage during World War II. The title, then, starts to seem ironic, an interpretation reinforced by the fact that there are no crowds present. The only person who is seen, a smiling driver, doesn’t even seem to pay attention to the gigantic inflatable balloon that ominously looms nearby. Does the celebratory spirit of the parade live on, even in its absence, or is something darker taking place? Weegee provides no clear-cut answer.

Tourmaline, Salacia, 2019

Mary Jones, the protagonist of this film, was a real-life Black trans woman sex worker who in 1836 was convicted of grand larceny in New York and sentenced to five years in Sing Sing. Tourmaline’s take on Jones’s life intentionally tweaks the historical record. In her film, Jones lives not in SoHo but in Seneca Village, a 19th-century haven for free Black Americans and Irish immigrants that was demolished to make way for Central Park. In adapting Jones’s life in this way, and in presenting it in an experimental mode that is far from a biopic, with split screens and lack of a cause-and-effect structure, Tourmaline liberates Jones, granting her more freedom than she ever had when she was alive. Although nearly two centuries have passed since Jones was imprisoned, Tourmaline connects Jones’s New York to the Manhattan of the present by including appropriated footage of trans figures like Marsha P. Johnson, an activist and drag queen associated with 1969’s Stonewall Uprising, which spurred the gay liberation movement in the United States.

Bernadette Mayer, Memory, 1971

The snapshots of New York that can be seen in Bernadette Mayer’s Memory are often shoddily composed, slightly out of focus, and deliberately a little grainy. Seen together, these amateurish shots form a moving attempt to pin down banal places and people that may otherwise have gone uncaptured. Each day, starting in July 1971, Mayer shot one roll of 35mm film while also keeping a diary of what she did. In total, she took 1,100 photographs; she also recorded hours of audio in which she read her poetry. (She likened the project to a film because of its combination of images and sound.) Among her pictures are some beautiful images: a woman looking forlorn at a hot dog stand, a blazing firecracker at a pier, two people walking across a sidewalk lined with fallen sheets of paper. Memory, which has also been published as a book, marks one way of using art to create a permanent image of a city in flux.

Yuji Agematsu, 01-01-2014 ~ 12-31-2014, 2014

Every day, Yuji Agematsu walks around the streets of New York and picks up specimens found along the way—a half-eaten hard candy, perhaps, or cracked plastic fingernails. He often places the day’s findings in the cellophane of a cigarette box, with each constituting a unit that Agematsu has called a “zip,” and he typically exhibits them in groups denoting either a month or a year of walks. Presented in rows on shelves in a quirky riff on Minimalism (Agematsu has long worked at the studio of Donald Judd, a leader of that movement), the “zips” become a way of marking time.

They also attest to the diversity of New York, where so many things and so many people are packed so densely that every encounter feels fresh. These are, after all, personal takes on the city’s landscape—Agematsu has curated them, in a sense. Accordingly, it’s not hard to imagine the joy he must have felt when he came upon the clump of moss, the unused condom, the perfectly preserved dead dragonfly, and the other items enlisted for this installation, which memorably appeared in 2015 at the now-defunct Brooklyn gallery Real Fine Arts.

John Knight, Identity Capital, 1998

This unassuming conceptual artwork at first appears to be an arrangement of 20 bouquets. Text accompanying each one makes clear that these aren’t just any flowers: They came from SoHo restaurants that held significant clout at the time—Balthazar and Odeon, to name two. Meanwhile, at these eateries, a note was left stating that the bouquets had been removed and transported to American Fine Arts, the famed New York gallery where the piece debuted. This method of presentation vaguely recalls how institutions inform the public of art typically on view that has been sent out on loan, drawing a line between the value of works and the social capital associated with these cafes. That all of the restaurants were located in what was at the time the city’s hottest gallery district is no coincidence either. Identity Capital asks a provocative question: What really counts most in the New York art world, a name or an object associated with it?

Paulo Nazareth, Sem título, 2011

Over the course of eight months in 2011, Paulo Nazareth went on an epic journey that involved going from Minas Gerais, Brazil, to the United States solely by foot and bus. His painstaking trek was documented in a photography series called “Notícias de América,” which immortalizes the various performances that Nazareth staged along the way. In this picture, Nazareth can be seen standing on a midtown street with the Empire State Building in the background. Wearing a head covering, a scarf, and a long white robe, he has a sign hanging around his neck: “DONT FORGET ME WHEN I WILL BE AN IMPORTANT NAME.” (Another shot features him donning the same sign in its Spanish equivalent.) Notably, the people walking by appear to barely register this Afro-Brazilian artist, who looks less like a figure with art world credentials than just another nomad passing through. Nazareth is questioning what it takes to really make it in a city like New York, where there are many others like him awaiting their turn in the spotlight.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, New York, 1957

When Gordon Parks visited crime scenes and prisons across the country for the photo essay “The Atmosphere of Crime” in 1957, he seemed less interested in arrests and the like than in everything around them. As part of that series, he produced works such as this photograph, in which a police officer is shown from behind. Shot in delicious color, with the dusky sky a deep shade of azure, the picture is dominated by an authority figure who seems to hold too much power, looming larger than any of the people who move down the street. That cop sucks the color from the photograph, leaving a black void at its center, even as the word MAJESTIC appears lit up on a nearby marquee. In composing the image in this way, Parks hints at the imbalances between regular people and the cops who police them.

Beauford Delaney, Can Fire in the Park, 1946

Because of the way that Beauford Delaney paints the shaky surroundings of Can Fire in the Park, it’s not exactly clear where these men are huddled. They stand before a trash fire, warming their spindly hands over flames amid trees, a manhole, and some arrows, which may connote street signs. Their faces aren’t visible, perhaps to indicate that they could be anyone—even Delaney himself. Delaney, who was based in Harlem at the time he made this work, faced poverty, and there is conjecture that the painting may represent a sight seen while spending the night on a park bench, according to its owner, the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Do Ho Suh, 348 West 22nd Street, 2011–15

For 19 years, Do Ho Suh lived in an apartment in the midtown neighborhood of Chelsea. Once he left it, he returned to the space in a metaphorical sense for this installation, which comprises exacting replicas of his unit, along with an adjacent hallway and staircase. However, these replicas aren’t quite the apartment as it appeared when Suh resided there—they’re formed from translucent polyester, they’re devoid of furniture, and the walls sag a little. Some viewers may feel a sense of alienation similar to what Suh has said he experienced as a person born in South Korea who has lived most of his life abroad. But even though the remade apartment seems machine-produced (Suh enlisted 3D imaging technology to get the most precise look possible), the artist lent it a human quality by sewing his fabric by hand.

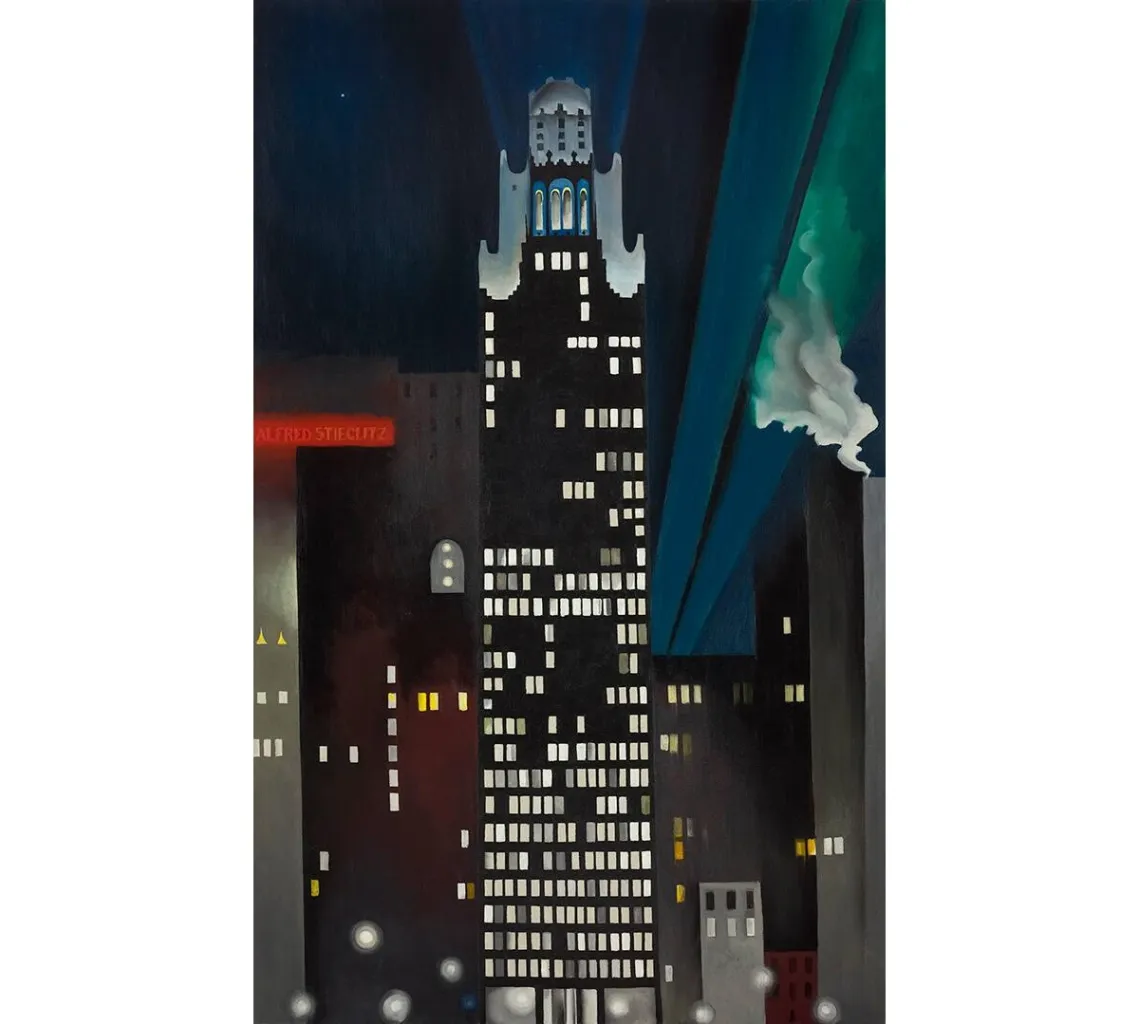

Georgia O’Keeffe, Radiator Building—Night, New York, 1927

At the time that Georgia O’Keeffe painted this work, the American Radiator Building was just three years old—a relatively new addition to a city that lacked many of the skyscrapers it now contains. A shining symbol of modernity, it acts as a literal beacon in this piece, in which O’Keeffe portrays the building as a sleek, fashionable tower whose windows offer illumination in a mostly dark landscape. O’Keeffe portrays other structures around it, but none are quite so captivating as this one, with its ornate Art Deco top that shoots blue light into the night sky. In O’Keeffe’s vision, the building dissolves into abstraction, fulfilling many modernists’ hope of realizing utopian cities without the use of figuration.

Romare Bearden, The Block, 1971

When making work, Romare Bearden once said, he “moved where my imagination took me.” That was how he came up with The Block, a raucous, tender tableau in which a couple make love, a sidewalk funeral takes place, and musicians play. In typical form for Bearden, those various figures are collaged, with their faces composed of overlapping elements that recall Cubism, the modernist movement in which objects were portrayed from multiple perspectives at once. In working in that method, Bearden shows that a city block rarely appears static. Although this 18-foot-long work represents an actual block in Harlem along Lenox Avenue between 132nd and 133rd Streets, it can hardly be said to represent reality—a Black angel can be seen in one apartment window, and the buildings themselves are rendered in bright hues that can’t be found on the street.

Linda Goode Bryant, Project EATS, 2009–

Linda Goode Bryant may be best known for forming a core New York art space, the short-lived but influential gallery Just Above Midtown, which made a priority of supporting Black, Asian, Latinx, and Native American artists. Since that gallery’s closure in 1986, Bryant has continued working as an artist and filmmaker, undertaking efforts such as Project EATS, an endeavor that may appear nothing like an artwork at all. Founded in 2009 and still active today, Project EATS bills itself as a “living installation” that provides “art that feeds.” It has set up farms with the aim of offering food to New Yorkers in neighborhoods that have occasionally gone overlooked by politicians, such as Brownsville, East Harlem, and Belmont, which are home to significant Black populations. Bryant has spoken of Project EATS as a community-led project. In a 2019 New York Times interview, she said, “Did I know anything about growing food before I started Project EATS? Hell no. But I figured it out.”

Pacita Abad, L.A. Liberty, 1992

Of the many representations of the Statue of Liberty throughout art history, few look quite like Pacita Abad’s L.A. Liberty. Abad, a Filipina artist who has spent much of her career in the United States, reiterated the common image of the statue as a gleaming beacon of immigrant pride, with one key twist: Lady Liberty is no longer a white woman. Abad said her image of Lady Liberty, done using a style that involved stuffing and stitching her canvas, was intended to recognize how many immigrants had not passed Bartholdi’s statue on their entry into the country, given that there were many African, Latino, and Asian immigrants who did not arrive via Ellis Island. Her radiant work suggests a more inclusive vision of one of New York’s most distinctive landmarks—an image that immigrants like herself may see themselves reflected in.

Maria Thereza Alves, Seeds of Change: New York—A Botany of Colonization, 2017

Ballast—the gravel, sand, and other materials used to stabilize ships—is hardly ever considered central to New York history, but for Maria Thereza Alves, it acted as an entry point for considering the influx of people and organic matter to the city over the centuries. Because the people manning the ships that came to New York used whatever was available on the ground to add weight to their vessels, they sometimes accidentally scooped up various species of plants endemic to the places from which they came. In so doing, they accidentally created records of their voyages in what they left behind. Through maps, lists, and actual plants themselves, Alves highlighted the movement of freed Blacks and a Norwegian immigrant while also pointing out the ways that gentrification and colonialism could be seen in ballast found today in New York. “I came to see the plants as witnesses, not only to trade and travel, but also to invasions, massacres, enslavement, immigration, war, and real estate development,” Alves told Art in America.

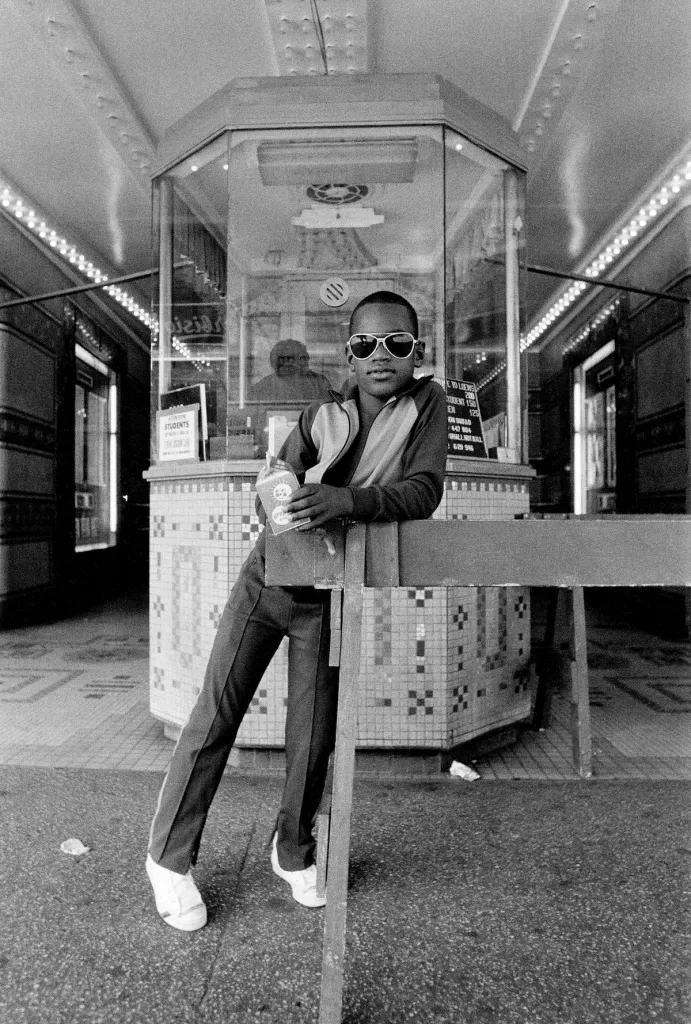

Dawoud Bey, A Boy in Front of the Loews 125th Street Movie Theater, 1976

Between 1975 and 1979, Dawoud Bey produced some essential photographic documents of the neighborhood he called home, in a series called “Harlem, U.S.A.” Working within a tradition of Harlem photographers that includes James Van Der Zee and Kwame Brathwaite, Bey was able to obtain a different, more intimate view of Harlem because he established sustained relationships with the people who passed before his camera. In this picture, taken on one of the busiest streets in Harlem, Bey shows a stylish boy sporting sunglasses in front of a ticket booth. With a cool, debonair demeanor, the boy leans against a sidewalk barricade and confidently looks at the camera, daring viewers to see him for who he really is.

Frida Kahlo, My Dress Hangs There, 1933

When Frida Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera, came to New York in 1931, they arrived in a Depression-era city that was rife with class divisions. These economic imbalances, combined with Kahlo’s own sense of alienation, informed My Dress Hangs There, a painting that represents a jumbled-up New York that is geographically inaccurate on purpose, with Wall Street situated before both the Statue of Liberty and Midtown.

In front of Federal Hall, collaged elements show the long bread lines that were forming in New York at the time; above them hangs the painting’s titular dress, a garment that stands in for the Tehuantepec culture whose matriarchal nature attracted Kahlo. The Tehuana dress seems at odds with the smokestacks and skyscrapers behind it and implies the irreconcilability between Kahlo’s Mexican roots and her temporary American home. The absurdist elements around it—an open toilet atop a column, an automaton with hand sassily placed on hip—point up the strangeness of Kahlo’s situation, which is felt by many foreigners who have come to New York.

ARTnews was not able to obtain permission to run an image of My Dress Hangs There, which is held in the FEMSA Collection and which has appeared publicly in several museum exhibitions, including one in 2019 about Kahlo’s identity that appeared at the Brooklyn Museum. An image of this work can be found here.

Zoe Leonard, Analogue, 1998–2009

In the course of more than a decade, Zoe Leonard took the 412 shots that compose this installation, sometimes using a Rolleiflex camera from the 1940s. That camera stood in sharp opposition to the digital devices that had become popular by the time Leonard started Analogue. This was very much the point—she wanted to activate a relic of the past as a mean of exploring how people and things grow outmoded.

Leonard started by photographing storefronts on the Lower East Side, offering up relatively straightforward images of sites such as bodegas and dress shops. Later, she expanded the project, journeying to Africa, the Middle East, and many places in between. Many of the sites she photographed, both in the New York neighborhood she called home and elsewhere, were not long for this world—they were getting pushed out by newer, shinier businesses. In memorializing these places on their deathbed, Leonard proposes that gentrification may wash away layers of history, but photography can counter the total erosion of a city’s cultural memory.

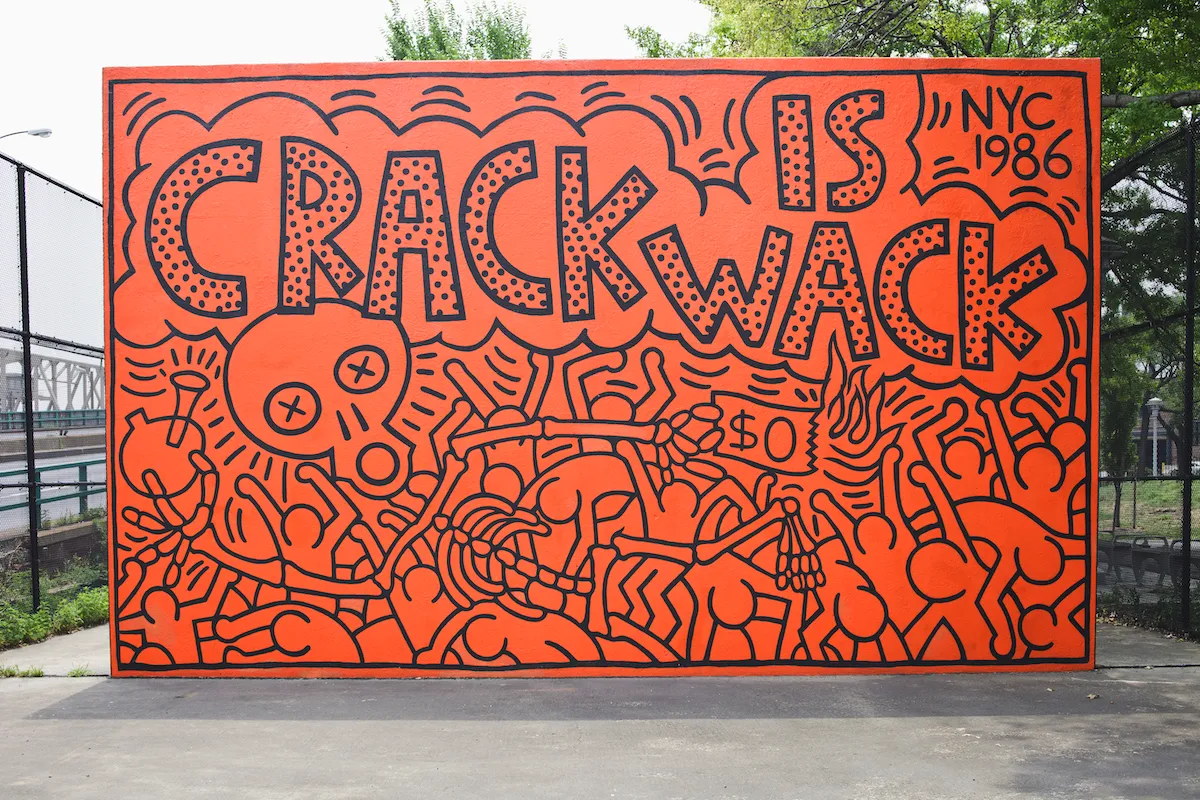

Keith Haring, Crack Is Wack, 1986

Although this mural is now one of the most recognizable pieces of public art in New York, city officials weren’t always so receptive to the graffiti-like work. In fact, the first time Haring painted Crack Is Wack on a handball court wall in East Harlem, he was made to pay a reduced fine of $25 for defacing public property, and the work was even painted over. This current iteration, which was restored in 2019, was painted again by the artist himself, with some alterations: He deleted elements such as an upside-down cross and a figure being dangled into the mouth of a sharp-toothed creature.

The sentiment remains the same, however. When Haring painted Crack Is Wack, the East Harlem neighborhood, like many others in cities across the United States, was in the throes of a crack epidemic. Using a Pop-inflected style that can be seen in many of his other artworks, Haring urged Harlemites not to take up the drug, which he posited as a money-sucking death machine, as seen by the skeleton holding a blazing dollar bill. Today, when the piece is seen by drivers coming down the Harlem River Drive, the mural retains its power.

Papo Colo, Against the Current, 1983

By the turn of the 20th century, the Bronx River had been designated an open sewer because it was so contaminated. It wasn’t until much later, during the 1970s and onward, that proper action was taken to highlight the amount of waste floating through it. Papo Colo’s performance Against the Current was in part an effort to draw attention to all the trash in the river. In it, the artist sat in a canoe and paddled upstream, in the process navigating through and around debris and pollution. Prior to this work, Colo had done other performances in which he threw himself into endurance-testing situations that were intended to communicate the strain that Puerto Ricans in New York often feel. This one functioned similarly. In addition to making works such as this one, Colo and his wife, Jeanette Ingberman, ran Exit Art, one of the city’s most famous alternative spaces.

Nona Faustine, From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth, 2013

A 1730 print shows the New York harbor near a bustling slave market in lower Manhattan; ships vie for spots to dock, and a crowd of people masses around a pavilion where a sale is taking place. These days, the area that this market once occupied, at the intersection of Wall Street and Water Street, is in a part of the city’s Financial District, but artist Nona Faustine reclaims its history in a series of photographs in which she pictures herself standing near New York sites related to the slave trade, often in various states of undress.

In this photograph, she stands on a wood block as traffic rushes around her. Faustine has described approaching the block while wearing a cape. A white male collaborator led her there and then removed it for her. The powerful image that results shows her defiantly looking into the camera, as if to suggest agency in a place where Black women like her had very little of it three centuries ago. Though her hands are shackled, she is wearing white pumps, implying some control over her image. Faustine has described experiencing a complicated set of emotions while creating the piece: “I watched as the people drove past me in their cars as if I, a Black woman, standing naked in the middle of the street, wasn’t even there at all.”

Florine Stettheimer, New York/Liberty, 1918–19

Florine Stettheimer painted many love letters to New York and its denizens throughout her career, none more affecting than New York/Liberty, a flattened view of Manhattan as viewed from the air looking north. As Stettheimer paints it, New York is a bustling metropolis with ships arriving in port and an airplane flying over skyscrapers. The patriotic sentiment is driven home not only by a waving American flag prominent on one vessel, but also by the frame, which eschews the traditional format for a less conventional painted pattern of red, white, and blue stripes, along with an eagle presiding over it.

Stettheimer suggests New York as a microcosm of the American experience, an idea driven home by the prominent placement in her tableau of Lady Liberty, whose dress appears sculptural because of the amount of paint Stettheimer has built up.

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021

Hart Island, in Long Island Sound and part of the Bronx, is an area of New York City that rarely is depicted. That may be because of its dark history: It has served as a public cemetery in times of crisis. People were buried there during the Civil War, the Spanish flu pandemic, and the AIDS crisis, and mostrecently it was where unclaimed bodies were laid to rest during the Covid pandemic. Coco Fusco’s video essay Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word renders that history present and unforgettable. In the video, which she began during the early stages of Covid, Fusco is shown alone, rowing a boat near the island. Periodically she throws carnations into the surrounding river, enacting what Fusco has said is a Catholic ritual intended to honor the dead.

But who, exactly, are the dead? The video mournfully suggests that there are limits to our knowledge in that regard, with its narrator, Pamela Sneed, saying: “They were herded through life as numbers, case numbers, file numbers, chart numbers, registration numbers, convict numbers, patient numbers. They are interred by men who also became numbers.” As Sneed says this, the camera flies over the island, offering a viewpoint intended to mirror the perspective of the deceased.

Robert Gober, Untitled, 2005

This work’s title alludes both to the day after the 9/11 attacks and to Robert Gober’s birthday, an unfortunate and unexpected coincidence. For this work, as well as similar ones by Gober, the artist makes use of New York Times spreads from September 12, 2001, the day after 9/11 and also Gober’s birthday. He then altered these spreads with drawn images of two figures.

In one of these works, beneath the headline “A Creeping Horror and Panicked Flight as Towers Burn, Then Slowly Fall,” bodiless pairs of legs are shown entangled in one another. They spill over onto reports on reactions to the attack, suggesting the possibility of rebuilding and the power of reunion amid so much violence. Few artists directly depicted 9/11, both at the time and in the ensuing years; this stands as one of the rare works to grapple with the enormity of the tragedy. Crucially, it implies that the only way for New Yorkers to begin moving forward is to do so together.

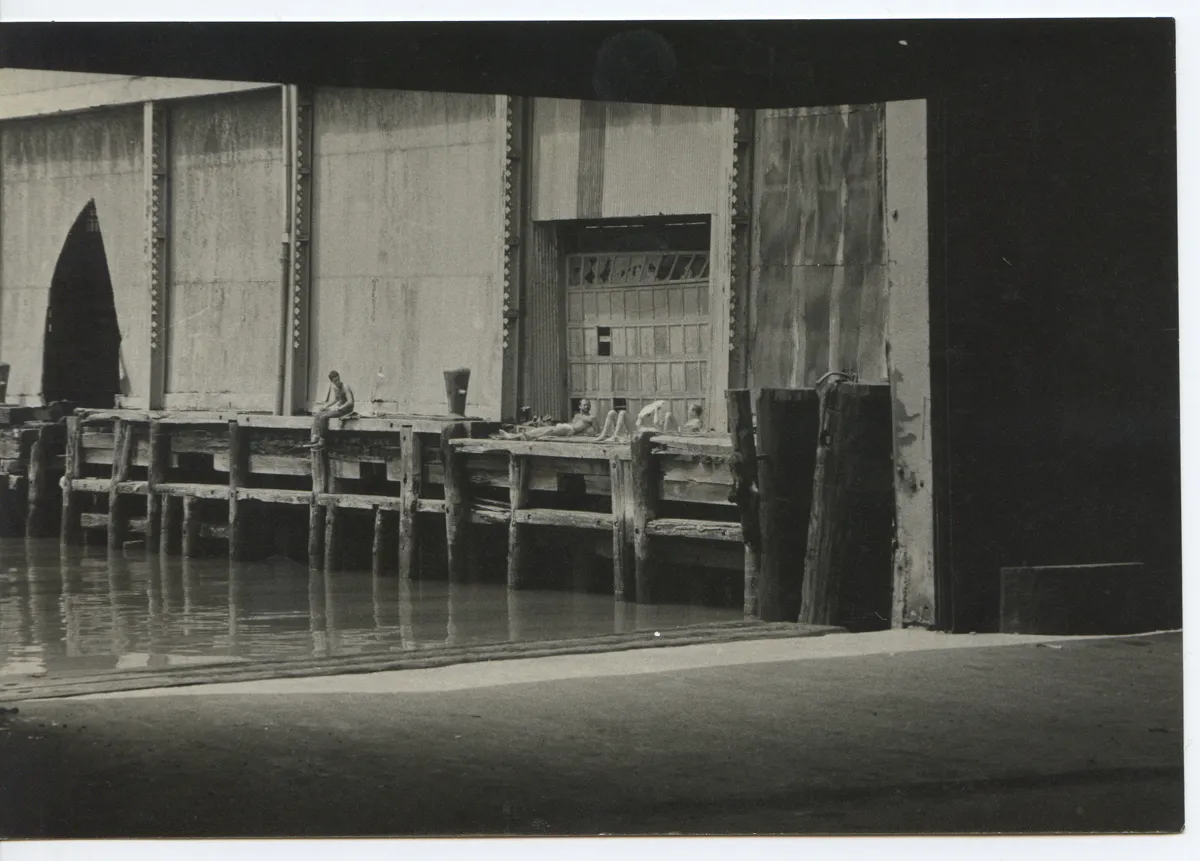

Alvin Baltrop, Pier 52 (four people sunbathing near Gordan Matta-Clark's Days), n.d.

During the 1970s, the piers on the Hudson River in Greenwich Village and the Meatpacking District became a playground for gay men, who flocked there to have sexual encounters just barely out of the public view. Alvin Baltrop bore witness, using his camera to record the dilapidated settings, the men who were drawn to them, and sometimes even their intercourse, which he voyeuristically pictured in graphic detail. Even when there is what art historian Douglas Crimp once called a “just-discernible scene of butt-fucking or cock-sucking,” Baltrop seems just as interested, if not more so, in the run-down surroundings.

That’s the case in this undated photograph, in which the walls of a pier frame semi-nude men who lounge by the Hudson River. Shooting from afar, Baltrop allows viewers to look on while offering these men a small amount of privacy. Since this picture was taken, the piers have gentrified. Yet Baltrop’s photographs linger on, acting as documents of the people who found community in a largely unused corner of Manhattan.

Simone Leigh, Free People’s Medical Clinic, 2014

While Simone Leigh is now better known for her sculptures, she received some of her first major acclaim for the Free People’s Medical Clinic, a functioning community center and clinic that was active in 2014 in Brooklyn’s Weeksville neighborhood. The location was not coincidental: Weeksville was founded by freed African Americans in the 19th century, and Leigh’s piece took place at Stuyvesant Mansion, where Josephine English, the first Black female ob-gyn doctor in New York, once lived.

In tribute to English’s work, as well as to the clinics set up by the Black Panthers during the 1960s and the semi-secret Black nurses’ group United Order of Tents, Leigh offered medical testing, acupuncture sessions, performances, dance classes, and more to the local community, whose members, she noted, have often been underserved by the medical establishment. The center may no longer be in operation, but that it existed at all is a testament to the strength of Weeksville’s citizenry.

Berenice Abbott, New York at Night, ca. 1933

Nari Ward, Amazing Grace, 1993

A sense of loss is palpable the second one enters Amazing Grace, Nari Ward’s well-known work assembling more than 300 used baby strollers. Technically, each of those strollers had actually served more than one user. Having been tossed out by their initial owners, they were then taken up by the unhoused, who used them to carry their belongings. Ward had planned to show these strollers in a church, a setting that would befit the hymn sung by Mahalia Jackson that accompanied the installation, but he instead settled for a firehouse in Harlem, where he placed them amid hoses.

The installation is cast mainly in darkness, and various interpretations have been given to the strollers’ arrangement. Many have said their display resembles a womb, while others have stated that the strollers are packed in like enslaved people transported by ship. In either case, the work mournfully underlines the tenuousness of some people’s existences in New York.

Diane Arbus, Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C., 1962

Diane Arbus was always interested in those on the fringes of society, and so it seems notable that in this unsettling image taken in Central Park, a boy is shown seemingly without his parents around. He appears to exist on his own, clutching a faux grenade in one hand and contorting his face in a jokey expression of angst. That Arbus seems to have caught the boy on the fly, with one suspender strap drooping down his shoulder, only adds to the mystique.

In actuality, this boy was no outcast—he was Colin Wood, son of the famed tennis player Sidney Wood. Still, Colin once told the Washington Post that the photo reflected “a general feeling of loneliness, a sense of being abandoned.” It seems telling, then, that the few visible figures in the background are captured out of focus. The picture is Arbus’s greatest statement about a city filled with outsiders who have infiltrated the mainstream, only to find themselves spat back out by it.

In keeping with the Arbus estate’s wishes, ARTnews did not reproduce an image of Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. This work can be found on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which owns it.

Orian Barki and Meriem Bennani, 2 Lizards, 2020

The Covid lockdown in 2020 spurred what may have been one of the most bizarre chapters in New York history, leaving typically bustling spaces like Times Square and Grand Central Terminal nearly vacant for several months. Orian Barki and Meriem Bennani met the weirdness of the moment with 2 Lizards, a video split into parts that were released on Instagram during lockdown rather than being shown in a gallery.

The titular computer-generated reptiles are shown in a city populated entirely by animals that meditate on social distancing, Zoom birthdays, and mask wearing. In many scenes, they are shown traversing an emptied city. But while everyone was shut inside, that didn’t mean the city was drained of its spirit, however, and 2 Lizards is a testament to the various forms of resilience and community that continue to exist even in the worst of times. It’s filled with memorable scenes such as one in which Barki and Bennani’s lizards venture up to their roofs and take part in a makeshift outdoor concert happening all across the block.

Roy DeCarava, Hallway, 1953

Many of Roy DeCarava’s photographs embrace darkness, which he prized for the way that it could produce so many different tonalities. The darkest of all the pictures he took, Hallway, features a corridor that seemingly extends deep into the distance, a set of lights providing small, barely useful spots of illumination along the way.

For DeCarava, the hallway’s foreboding quality returned him to his upbringing in Harlem. “When I saw this particular hallway I went home on the subway and got my camera and tripod, which I rarely use,” he once said. “The ambience, the light in this hallway was so personal, so individual that any other kind of light would not have worked. It just brought back all those things that I had experienced as a child in those hallways.” In that way, the photograph represents a personal reflection on the neighborhood that DeCarava long called home. The picture and other works by DeCarava would go on to inspire the work of photographers associated with the Kamoinge Workshop, the Harlem-based photography collective he cofounded.

In keeping with the DeCarava estate’s wishes, ARTnews did not reproduce an image of Hallway. This work can be found on the website of the National Gallery of Art, which owns it.

Matthew Barney, Cremaster 3, 2002

Cremaster 3, the ambitious final film in a series called “The Cremaster Cycle,” spans three hours and multiple timelines. Making sense of what Matthew Barney offers up can be a challenge, but according to the summary supplied by the artist, the film is loosely about the architecture and history of the Chrysler Building, one of New York’s most iconic skyscrapers. Barney himself plays a character billed as the Entered Apprentice, who appears alongside the Architect, as played by the artist Richard Serra. The two perform rituals associated with the Freemasons revolving around the quest for universal knowledge.

As they spiritually, mentally, and sometimes physically ascend in this New York landmark, they transcend themselves by increasingly absurdist means. One rite involves a grouping of cars that rev their engines inside the Chrysler Building, a bizarre gesture that goes largely unexplained. The action climaxes in a sequence known as “The Order,” in which the Entered Apprentice surmounts a series of challenges on his way up the ramp of another modernist landmark in New York, the Guggenheim Museum. What exactly does any of it mean? The dense conceptual lore is either masterfully oblique or a lot of hooey, depending on whom you ask, but either way, Cremaster 3 hypnotically attests to the continued allure of two of the city’s most prominent buildings.

David Wojnarowicz, “Arthur Rimbaud in New York,” 1978–79

Arthur Rimbaud was a 19th-century French writer who famously had a relationship with the poet Paul Verlaine. A little under a century after Rimbaud’s death, another queer artist in another country, the New Yorker David Wojnarowicz, donned a mask of the writer’s face and wore it around the city. Wojnarowicz photographed the results for a series called “Arthur Rimbaud in New York,” which is now celebrated as one of the great works in the canon of queer art.

In taking on Rimbaud’s guise, Wojnarowicz suggested that the tragic conditions of Rimbaud’s life—the poet’s relationship with Verlaine turned ugly, and even violent—were not all that dissimilar to his own. In these pictures, Wojnarowicz ventures out to areas in New York that he knew well, including the piers, where he and other gay men cruised, and shoots himself looking out of place. The Rimbaud mask does not seamlessly fit over Wojnarowicz’s face, and it is difficult to know what emotions are passing through the artist because his expression is kept concealed. The effect is off-putting, with the city where Wojnarowicz was based acting not as a home but as an inhospitable backdrop.

Tania Bruguera, Immigrant Movement International, 2010–2015

The activities of Immigrant Movement International, a still-functioning community center in Corona, Queens, may not look much like art—they do not result in objects that can be exhibited in galleries. But for its creator, Tania Bruguera, the organization is an example of her concept of arte utíl, a form of art that can double as a kind of direct political action.

Conceived in collaboration with the art nonprofit Creative Time and the Queens Museum, and inspired by protests led by immigrants in a Paris suburb in 2005, Immigrant Movement International has a stated aim of functioning as “a think tank that recognizes (im)migrants’ role in the advancement of society at large and envisions a different legal reality for human migration.” (Nearly two-thirds of Corona’s population identifies as Hispanic or Latino; Bruguera herself immigrated from Cuba, where her art has been censored by the government.) Among the organization’s initial activities were readings of its Migrant Manifesto and actions related to Occupy Wall Street. Events like these put politics to work, merging activism and art.

Diego Rivera, Frozen Assets, 1931–32

The skyline of this mural by Diego Rivera isn’t quite accurate—Rivera transposed the placements of certain buildings, effectively remaking the city. That ought to be the first giveaway that Frozen Assets takes place in a fantastical world that only loosely corresponds to reality. The work, one of several Rivera created for the Museum of Modern Art after coming to New York from Mexico City in 1931, is separated into thirds, depicting the skyline, the Municipal Pier on 25th Street, and a Wall Street bank vault. In segmenting the mural this way, Rivera comments on the economic stratification felt in the city during the Great Depression.

The picture Rivera offers of this Depression-era New York is a bleak one. In the Municipal Pier, a cop stands watch as rows and rows of people lie on the floor. Because of their pallor, these bodies look like corpses until you realize that some have propped themselves up. In fact, most are just sleeping. Further below is the place where all the city’s wealth lies, locked away from the commoners. Although the painting may tilt into allegory, it does, at least, have one true character in it. The man sitting on a bench outside the vault is believed to be John D. Rockefeller, a major funder of MoMA, which temporarily put the work back on view in 2011, nearly 80 years after its debut.

Danh Vo, We the People, 2011–16

Before he created a complete replica of it, Danh Vo had never actually seen the Statue of Liberty in person. Still, the Vietnamese-born artist was always drawn to the repoussé technique that Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi used to produce his bronze statue, which lent it a surprisingly fragile quality. This stood in sharp contrast to the statue’s hard, stoic look, which Vo literally deconstructed by hiring a Shanghai fabricator to reproduce the Statue of Liberty in 250 parts. He ultimately exhibited those pieces in their unassembled form.

Seen in isolation, the individual pieces of We the People are abstract—folds of fabric, oversize fingers, bits of a torch that look odd, even foreign. Dematerialized and re-formed, and produced by people spanning multiple continents, Vo’s Statue of Liberty is in some ways even truer to its pro-immigration stance than the real thing. If We the People looks to the past for inspiration, however, Vo has stated that the work is really about what’s to come, anticipating an increasingly globalized future.

David Hammons, Higher Goals, 1986

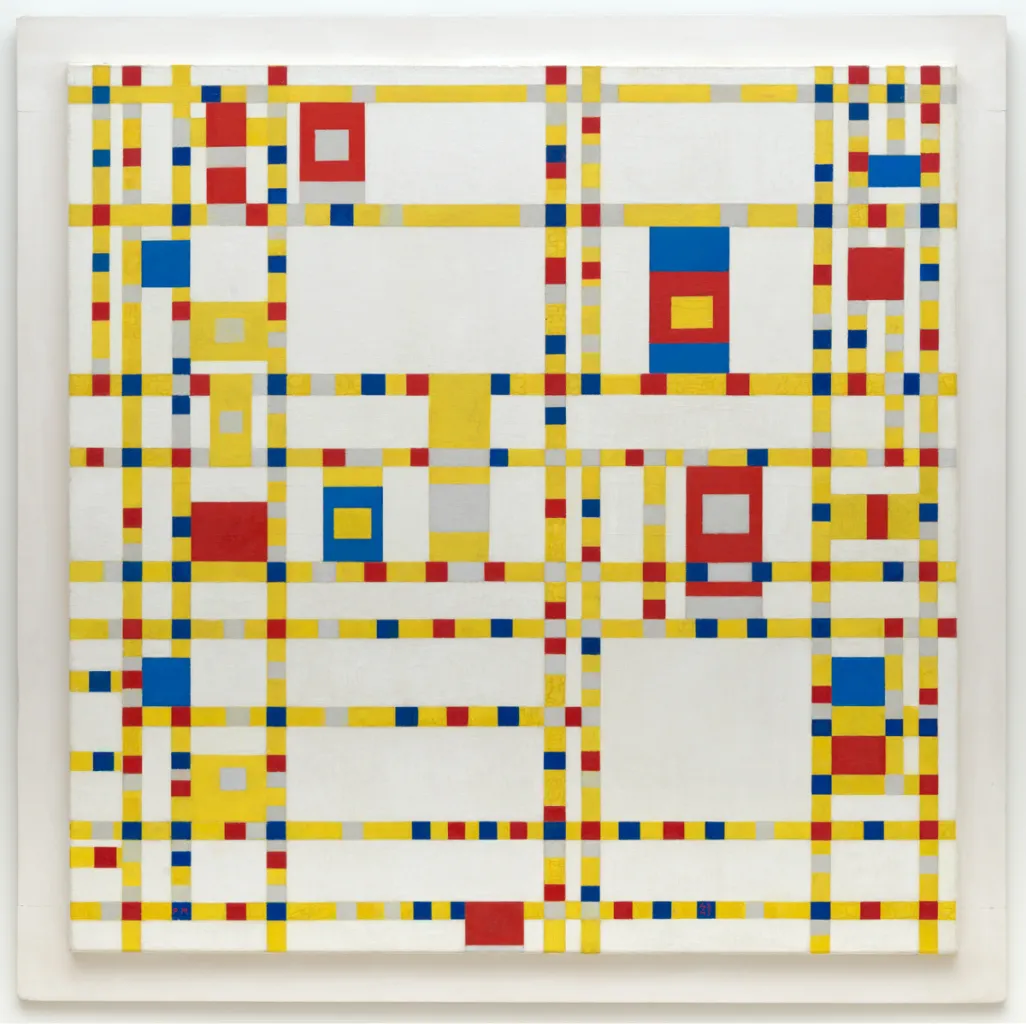

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942–43

On the first night he spent in New York in 1940, the year he fled London as it was drawn into World War II, the Dutch-born Piet Mondrian heard sounds he had never experienced before: boogie-woogie music. Inspired by its jagged, fast-paced rhythms, Mondrian began drawing on the style for his own modernist abstractions and applying it to his vision of the city he now called home.

Broadway Boogie Woogie is one such work. It features a bird’s-eye view of a Manhattan grid, its blocks reduced to masses of white periodically interrupted by red, yellow, and blue buildings. Those same hues dot the streets, like cars seen from above. Because of the painting’s coloration, it’s not hard to almost hear this abstraction, as the composer Jason Moran once did, likening it to a jazz score. There aren’t many artworks that both look and sound like New York; this synesthetic quality is what makes Mondrian’s evocation so memorable.

Martha Rosler, The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1974–75

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), 1983

In 1983 Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old artist who’d gained notice in the New York art scene, was arrested by cops who said he was painting graffiti in an L train subway station. By the time Stewart was taken to a nearby precinct house, he had been handcuffed, bound up, and rendered comatose after being beaten. Students at a nearby Parsons School dormitory said they heard his screams. He was arrested for marijuana possession and was pronounced dead 13 days later due to a spinal injury.

The impact of Stewart’s death rippled through New York, touching Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was so moved by it that he reportedly told friends, “It could have been me.” Basquiat processed his grief with Defacement, a horrific vision of police violence in which two cops wield batons against a black figure with no facial features. “¿DEFACEMENT©?” reads the text above this brutal image, questioning whether the accusations levied against Stewart by members of the NYPD were really true. Although the piece hardly evinces a documentary aesthetic, it can be seen as a means of reporting the facts about a particularly dark chapter of ongoing New York history. “This was a time before social media, and this was a kind of evidence,” curator Chaédria LaBouvier, who organized a 2019 Guggenheim Museum show about the work, once said. “I think they wanted to make sure it wasn’t forgotten.”

ARTnews was not able to obtain permission to run an image of Defacement, which is owned by Nina Clemente and which has appeared publicly in several museum exhibitions, including the 2019 Guggenheim show. An image of this work can be found here.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1981–1982 (Outdoor Piece), 1981–82

From September 1981 to September 1982, Tehching Hsieh spent 8,760 hours outside in New York, braving a harsh winter and, at one point, an arrest by the police. (The Taiwanese artist was then undocumented; he pleaded with the police to leave him be. They did not, but a judge proved more sympathetic.) During that time, Hsieh lived nomadically, with a sleeping bag and a backpack containing supplies as his only possessions. “I shall not go in to a building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent,” he wrote in the statement that guided the work. For the most part, he succeeded.